The Sir John Franklin voyage of 1845 is one of the most famous—and tragic—expeditions of the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration, and it was important for several interlinked reasons:

⸻

1. Imperial Ambition and the Search for the Northwest Passage

• Britain was at the height of its naval power in the mid-19th century. Securing the Northwest Passage—a sea route linking the Atlantic and Pacific through the Arctic—would provide enormous strategic and commercial advantage.

• Franklin’s expedition was the most ambitious attempt yet: two heavily reinforced ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, with steam engines, iron plating, and a supply of canned food intended to last three years.

• It symbolized the Royal Navy’s commitment to both science and empire.

⸻

2. Scale and Prestige

• The 1845 voyage was the largest and best-equipped Arctic expedition of its time, carrying 129 men and enormous resources.

• Franklin himself was already a respected explorer (“the man who ate his boots” from earlier Arctic expeditions), making this mission a matter of national pride.

⸻

3. Scientific and Geographic Goals

• Beyond finding the passage, the expedition aimed to chart unknown regions of the Arctic, gather natural history specimens, and make meteorological and magnetic observations.

• It was part of Britain’s wider push to map the world’s remaining “blank spaces.”

⸻

4. The Mystery and Tragedy

• Franklin and his crew disappeared. For more than a decade, search expeditions scoured the Arctic. These searches themselves led to major discoveries:

• Large portions of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago were mapped.

• Scientific knowledge of the Arctic climate, flora, fauna, and Inuit culture expanded dramatically.

• The mystery of the lost expedition captured the Victorian imagination, inspiring literature, art, and public debate.

⸻

5. Human Lessons

• Inuit testimony and later archaeological evidence revealed the crew succumbed to starvation, scurvy, lead poisoning (from poorly sealed canned food), and possibly tuberculosis. Evidence of cannibalism shocked Victorian Britain.

• The tragedy highlighted the limitations of European technology when set against the harsh Arctic, and the failure to draw on Inuit survival knowledge.

⸻

6. Enduring Legacy

• The Franklin disaster became a turning point in Arctic exploration: Britain invested decades in the search, pushing further into the polar regions than ever before.

• It remains a powerful symbol of human ambition, hubris, and endurance.

• In 2014 and 2016, the wrecks of Erebus and Terror were finally found, reigniting global interest in the story.

⸻

✅ In short: The Franklin voyage was important because it was the grandest British Arctic expedition, its disappearance sparked one of the largest search operations in history, it dramatically advanced geographic and scientific knowledge of the Arctic, and it left behind a cultural legacy of mystery, tragedy, and fascination that still resonates today.

After Sir John Franklin’s expedition landed at Beechey Island in the winter of 1845–46, the trail of events can be pieced together from archaeology, Inuit testimony, and later search expeditions. Here’s what is known:

⸻

🧊 Winter at Beechey Island (1845–46)

• The expedition’s two ships, HMS Erebus and Terror, anchored at Beechey Island (off the coast of Devon Island in Lancaster Sound).

• They wintered there, building stone fireplaces and workshops.

• Three crewmen (Petty Officer John Torrington, Royal Marine William Braine, and Able Seaman John Hartnell) died and were buried in marked graves.

• Archaeology shows the men suffered from lead poisoning, possibly from poorly soldered tinned food, and perhaps tuberculosis.

⸻

🚢 Southward Movement (Summer 1846)

• In the summer of 1846, the ships left Beechey Island and sailed further south and west through Lancaster Sound and Peel Sound.

• They became trapped in heavy ice off the northwest coast of King William Island.

• A note later found in a cairn on King William Island confirms they were beset by ice in September 1846 and unable to break free.

⸻

❄️ The Long Trapped Years (1846–48)

• The ships remained trapped in ice for almost two full years.

• During this time, Sir John Franklin died (June 1847). Leadership passed to Captain Francis Crozier of Terror.

• The men attempted hunting but suffered increasing weakness from scurvy, starvation, lead poisoning, and disease.

⸻

🏃 The Abandonment (April 1848)

• On April 22, 1848, 105 survivors abandoned the ships, leaving behind 9 dead officers and men.

• They attempted to march south along the western coast of King William Island toward the Back River (near the Canadian mainland), hoping to reach Hudson’s Bay Company outposts.

• They dragged heavy boats and sledges over ice, but conditions were catastrophic.

⸻

🪦 The Death March

• Inuit oral histories describe starving, exhausted men dragging boats southward, some collapsing and dying along the way.

• Archaeological sites and remains along the southern coast of King William Island show the men perished in small groups.

• Cut marks on bones indicate that some resorted to cannibalism—a shocking revelation when John Rae reported it in 1854, but later confirmed by modern forensic analysis.

⸻

⚓ Final Fate of the Ships

• Erebus and Terror were eventually abandoned to the ice. Inuit accounts suggest the ships drifted and one sank while the other remained intact for some time before also going under.

• The wrecks were rediscovered in modern times:

• Erebus in 2014 (near Wilmot and Crampton Bay)

• Terror in 2016 (in Terror Bay, remarkably well-preserved).

⸻

✅ In short: After Beechey Island, Franklin’s expedition pushed south into Peel Sound, became icebound off King William Island, Franklin died in 1847, the ships were abandoned in 1848, and the surviving crew attempted a desperate overland retreat—none survived.

the disappearance of Sir John Franklin’s 1845 expedition triggered one of the largest search efforts in history, spanning more than a decade (1848–1860s). These missions came by sea from both the Atlantic and Pacific, and by land across northern Canada. They were launched by the Royal Navy, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and even the United States — driven by national pride, science, and Lady Franklin’s tireless campaigning.

Here’s a structured breakdown of the major search parties:

⸻

1. Early Relief Expeditions (1848–1850)

• 1848 – Sir James Clark Ross (Britain)

• Sailed with Enterprise and Investigator via Lancaster Sound.

• Reached as far as Port Leopold (Somerset Island) but found no trace.

• Hudson’s Bay Company land expeditions (1848–49)

• Sir John Richardson and John Rae searched along the Mackenzie River and Arctic coast — no results, but Rae’s knowledge of Inuit survival would later prove vital.

⸻

2. The Major Search Wave (1850–1851)

• Royal Navy (Edward Belcher, Horatio Austin, Erasmus Ommanney, Sherard Osborn, etc.)

• Several ships explored Lancaster Sound, Barrow Strait, and Wellington Channel.

• Found Franklin’s Beechey Island winter camp (1845–46) with three graves — the first solid clue.

• American Expeditions (1850–51)

• Funded by Henry Grinnell (New York philanthropist).

• Commanders: Edwin De Haven and physician Elisha Kent Kane.

• Joined the British search in Wellington Channel, also visited Beechey Island.

⸻

3. Expeditions from the Pacific (1850s)

• Robert McClure (HMS Investigator, 1850–54)

• Entered from the Bering Strait.

• Trapped in ice near Banks Island.

• His sledging parties linked west and east surveys, making him the first to traverse the Northwest Passage (partly by sledge).

• Richard Collinson (HMS Enterprise, 1850–55)

• Also entered from the Pacific, explored around Victoria Island.

⸻

4. Further British Naval Searches (1852–54)

• Edward Belcher (1852–54)

• Led a massive squadron of five ships.

• Reached high into Wellington Channel and west toward Melville Island.

• Lost or abandoned four ships (including Resolute), earning a reputation for mismanagement.

⸻

5. Overland and Inuit-Guided Searches

• John Rae (Hudson’s Bay Company, 1853–54)

• Explored along the Canadian Arctic mainland.

• Crucially learned from Inuit of starving white men near King William Island.

• Collected artifacts (silverware with Franklin’s crest) and reported cannibalism — shocking Victorian Britain.

⸻

6. Final Confirmation of Franklin’s Fate

• Francis Leopold McClintock (1857–59, yacht Fox, financed by Lady Franklin)

• Reached King William Island.

• Found the famous Victory Point Note (1847 & 1848 messages) left by Crozier and Fitzjames.

• Retrieved relics, skeletons, and confirmed the crews’ desperate march south.

⸻

7. Later Searches and Legacies (1860s onward)

• Charles Francis Hall (USA, 1860s–70s)

• Lived among Inuit, collected oral histories about Franklin survivors and shipwrecks.

• Frederick Schwatka (USA, 1878–80)

• Led a sledging expedition, confirming and mapping Inuit accounts of Franklin’s men’s final march.

⸻

✅ In summary

The search for Franklin involved:

• Dozens of expeditions (1848–1880s) by Britain, the U.S., and the Hudson’s Bay Company.

• They mapped much of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, proved the existence of the Northwest Passage, and brought back Inuit testimony that revealed Franklin’s grim fate.

• Though Franklin’s men were never rescued, the search revolutionized Arctic exploration.

Beechey Island, though remote and windswept, is one of the most important historic sites in the Canadian Arctic because of its deep connection to the Franklin Expedition and other 19th-century voyages. Today, it’s part of Nunavut’s Territorial Historic Sites and is often visited on Arctic cruises.

Here’s what you can see there today:

⸻

🪦 Franklin Expedition Graves (1845–46)

• Three preserved wooden grave markers and memorials for:

• John Torrington

• William Braine

• John Hartnell

• The graves are in a small, poignant cemetery overlooking the bay. The original headboards have been replaced by replicas, with the originals stored in preservation.

⸻

🏛 Northumberland House Remains (1850)

• Foundations and traces of the storehouse built in 1850 by rescuers under Sir Edward Belcher during their search for Franklin.

• This became a supply depot for later expeditions and is sometimes called the “first house in the High Arctic.”

⸻

🪨 Memorials and Plaques

• A large memorial stone for Franklin and his men, erected in 1855 by Belcher’s search party.

• Additional plaques commemorating Franklin search expeditions, and one for the crew of HMS Investigator (Robert McClure’s ship).

⸻

🔥 Archaeological Remains

• Stone outlines of fire pits, tent rings, and workshops left behind by Franklin’s crew.

• Caches and debris from search expeditions of the 1850s and 1860s.

• Rusted barrel hoops, nails, and fragments of food tins still visible on the ground.

⸻

🏔 Natural Environment

• A stark Arctic landscape of gravel, permafrost, and low tundra.

• The surrounding waters are rich in wildlife: polar bears, seals, beluga whales, and nesting seabirds (like kittiwakes and fulmars).

• Despite its bleakness, it has a haunting atmosphere that reflects the human struggles that took place there.

⸻

🚢 Modern Access

• There are no permanent settlements or facilities on Beechey Island.

• It can be reached only by specialized expedition cruises, private vessels, or occasionally by chartered aircraft.

• Visitors must follow strict Parks Canada guidelines to protect the site.

⸻

✅ In short: On Beechey Island today you’ll find the Franklin graves, memorials, ruins of rescue depots, scattered relics, and a stark Arctic wilderness—a site both archaeological and deeply symbolic in the history of polar exploration.

Radstock Bay, just across from Beechey Island on the south coast of Devon Island (Nunavut), is one of the most historically and culturally rich stops in the Arctic. It has both Franklin history and deep Inuit heritage, making it a key site on Arctic voyages.

Here’s what there is to see today:

⸻

🧊 Franklin Expedition Connections

• Radstock Bay lies close to the route taken by Franklin’s 1845 expedition as it moved west from Beechey Island.

• While no direct Franklin camp has been found here, the area became important during 19th-century search expeditions, who often stopped in Radstock Bay for shelter.

• Many Arctic cruises today pair Beechey Island + Radstock Bay as a combined visit.

⸻

🏞 Caswell Tower (the Landmark)

• A striking flat-topped mountain (a mesa-like formation) rising above the bay.

• This landmark dominates the skyline and was used by explorers and Inuit as a navigational point.

• Hikes to its slopes or ridges give sweeping views of Lancaster Sound and Devon Island’s coastline.

⸻

🪨 Thule Archaeological Sites (Inuit History)

• The area contains ancient Thule Inuit dwellings (ancestors of today’s Inuit), dating back 500–800 years.

• Visitors can see the stone outlines of semi-subterranean houses built with whale bones, stones, and sod.

• Middens (refuse heaps) still contain remnants of tools, bones, and food remains, giving insight into Inuit life.

⸻

🐋 Whaling History

• The bay was also used by 19th-century European and American whalers.

• Ruins of whalers’ camps, cooperages (barrel-making sites), and tryworks (blubber-rendering hearths) can sometimes be identified.

⸻

🐦 Wildlife and Nature

• Radstock Bay is rich in Arctic wildlife:

• Seabirds nesting on cliffs (kittiwakes, fulmars, guillemots).

• Polar bears often patrol the shoreline.

• Walrus and seals in the surrounding waters.

• The landscape is tundra and gravel flats, with vibrant wildflowers in summer.

⸻

🚢 Modern Visits

• Today, Radstock Bay is a regular stop for Arctic expedition cruises, often paired with Beechey Island.

• Guided hikes take visitors to the Thule sites and up toward Caswell Tower.

• Parks Canada protects the archaeological remains, so visits are carefully controlled.

⸻

✅ In short: At Radstock Bay you’ll find dramatic landscapes (Caswell Tower), Inuit archaeological sites, traces of whaling and exploration history, and abundant Arctic wildlife — making it one of the most evocative cultural and natural stops in the High Arctic.

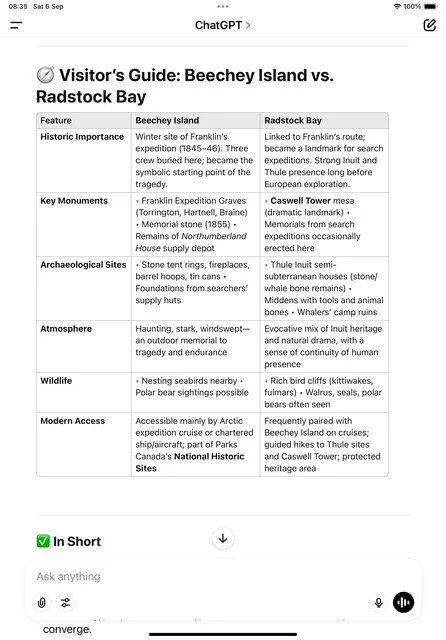

Feature

In Short

• Beechey Island: A solemn memorial site, tied forever to the Franklin tragedy and the search era.

• Radstock Bay: A broader cultural and natural site, where Inuit archaeology, exploration history, and dramatic Arctic landscapes converge.