Bradford

1. Photojournalism

• Purpose: To report news events quickly and truthfully, often for newspapers, magazines, or online outlets.

• Subject matter: Anything newsworthy — political events, disasters, sports, crime, human interest.

• Approach: Fast, reactive, fact-driven. Captions must be accurate, time-specific, and verifiable.

• Ethics: Strong emphasis on truth — no staging, no altering the scene, minimal editing beyond technical corrections.

• Typical output: Single impactful images or short series that illustrate a specific news story.

• Example: Bert Hardy covering the Korean War for Picture Post.

Key idea: Photojournalism is “photography as news”.

⸻

2. Documentary Photography

• Purpose: To tell a deeper, long-form visual story about social, cultural, or environmental issues.

• Subject matter: Often everyday life, social conditions, or long-term changes — not necessarily “breaking news”.

• Approach: Slower, more immersive. Photographers may spend months or years with a community or topic.

• Ethics: Still factual and honest, but may allow more interpretive composition or narrative sequencing.

• Typical output: Photo essays, books, exhibitions, or long-term projects.

• Example: Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother project documenting the Great Depression.

Key idea: Documentary is “photography as social record”.

⸻

3. Street Photography

• Purpose: To capture candid moments in public spaces, often exploring human behaviour, visual coincidences, or urban life.

• Subject matter: People, streets, architecture, everyday interactions — not necessarily tied to news or a social issue.

• Approach: Spontaneous, unposed, often shot without subjects’ awareness to preserve authenticity.

• Ethics: Less bound by journalism codes, but still values honesty of the moment. Can be more artistic or abstract.

• Typical output: Individual images or thematic series for artistic or personal expression.

• Example: Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” photographs.

Key idea: Street photography is “photography as candid observation”.

⸻

Where They Overlap

• Documentary vs. Photojournalism: Both aim for truth, but documentary tends to be slower and more thematic; photojournalism is faster and more event-driven.

• Street vs. Documentary: Street photography can become documentary if it’s sustained on a theme over time.

• Street vs. Photojournalism: Street photography may overlap with photojournalism when a candid public shot happens to be newsworthy.

Some of the key pioneers of street photography—the people who shaped the genre’s style, ethics, and visual language—include:

⸻

Early Foundations of street Photography(Late 1800s – Early 1900s)

• Eugène Atget (France) – Documented Paris streets, storefronts, and architecture with a quiet, observational style. Though often classed as documentary, his work influenced later street photographers like Berenice Abbott.

• Paul Martin (UK) – One of the first to photograph people candidly on the streets of London in the 1890s using a concealed hand camera.

• Alfred Stieglitz (USA) – Captured street life in New York around 1900, often blending urban scenes with a sense of modernism.

⸻

Interwar Years (1910s – 1930s)

• André Kertész (Hungary/France/USA) – Known for lyrical, spontaneous compositions that found poetry in everyday street life.

• Brassaï (France) – Famous for Paris de Nuit (1933), revealing the hidden nighttime world of Paris’s streets, cafés, and back alleys.

• Walker Evans (USA) – Though primarily a documentary photographer, his candid subway portraits and New York street scenes influenced the candid tradition.

⸻

The Decisive Moment Era (1930s – 1950s)

• Henri Cartier-Bresson (France) – Perhaps the most influential street photographer; his “decisive moment” philosophy became a defining ethos of the genre.

• Helen Levitt (USA) – Captured New York street life, especially children’s play, with empathy and a painterly eye.

• Robert Doisneau & Willy Ronis (France) – Romantic, humanist street images of postwar Paris.

• Weegee (Arthur Fellig, USA) – Hard-edged night-time street and crime photography in New York.

⸻

Postwar to Modern Expansion (1950s – 1970s)

• Garry Winogrand (USA) – Dynamic, often chaotic New York street scenes; pioneered shooting from the hip.

• Diane Arbus (USA) – While more portrait-oriented, her work engaged with people in public spaces in ways that challenged conventions.

• Tony Ray-Jones (UK) – Captured eccentricities of British seaside and street life with humor and sharp observation.

• Joel Meyerowitz (USA) – Introduced color into serious street photography in the 1960s, shifting the genre away from black-and-white dominance.

⸻

📌 In short:

• Atget → Kertész → Cartier-Bresson → Winogrand forms a direct lineage in technique and philosophy.

• The European “humanist” tradition (Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Levitt) emphasized empathy and storytelling.

• The American postwar wave (Winogrand, Meyerowitz) pushed towards energy, experimentation, and color.

In recent years, several photographers have pushed street photography in new directions—often blending it with conceptual art, social commentary, or digital experimentation.

Here are some of the most notable contemporary pioneers (1990s–today):

⸻

Color, Energy & New Perspectives

• Alex Webb (USA) – Known for his rich, layered color compositions, often in Latin America and the Caribbean, which redefined how color could be used in street photography.

• Raghubir Singh (India, active until 1999) – Brought Indian street life vividly into the global scene through complex, colorful frames.

• Harry Gruyaert (Belgium) – Magnum photographer whose bold color and light play in Morocco, the USA, and Europe influenced many in the digital era.

⸻

Humor & Humanity

• Martin Parr (UK) – Combines sharp humor and social critique, documenting British life and beyond with saturated color and a satirical edge.

• Matt Stuart (UK) – Modern master of perfectly timed visual puns and playful compositions on the streets.

⸻

Urban Grit & Candid Intensity

• Bruce Gilden (USA) – Famous (and controversial) for his in-your-face flash street portraits; influenced a generation of more aggressive street shooters.

• Boogie (Vladislav Gubarev) (Serbia/USA) – Dark, raw images of urban subcultures, from Brooklyn gangs to Belgrade streets.

⸻

Women Reshaping the Field

• Vivian Maier (USA, work discovered posthumously) – Now considered one of the greats, her vast archive has inspired many contemporary photographers.

• Nguan (Singapore) – Quiet, pastel-toned street portraits that contrast with the traditional gritty aesthetic.

⸻

Digital & Global Influences

• Rui Palha (Portugal) – Uses both digital and film to capture Lisbon’s evolving streets with a mix of classic and modern style.

• Eric Kim (USA) – Noted for making street photography accessible through workshops, blogs, and social media.

• Gueorgui Pinkhassov (Russia/France) – Magnum photographer whose abstract, color-rich images feel modern despite being shot mostly on film.

⸻

📌 Key differences from earlier pioneers:

• Strong use of color as a primary compositional element (vs. early dominance of B&W).

• Social media and online communities (Flickr, Instagram) allow new styles and micro-movements to spread quickly.

• A greater range of approaches to ethics—from deeply intimate consent-based portraits to confrontational flash work.

Photojournalism emerged in the mid-to-late 19th century when advances in cameras, printing, and transportation made it possible to capture and publish timely images of news events.

Some of the key pioneers include:

⸻

📜 Early Foundations (Mid–Late 1800s)

• Roger Fenton (UK) – Covered the Crimean War in 1855; one of the first war photographers, though his images were carefully staged for public consumption.

• Mathew Brady & Alexander Gardner (USA) – Documented the American Civil War in the 1860s; brought the reality of war into public view.

• Felice Beato (Italian–British) – Photographed wars and conflicts in Asia, including the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the Second Opium War; among the first to photograph in East Asia.

⸻

📰 Birth of the Illustrated Press (Early 1900s)

• Jacob Riis (Denmark/USA) – Used flash photography to expose New York’s slum conditions in How the Other Half Lives (1890).

• Lewis Hine (USA) – Social reformer who photographed child labor, immigrants, and workers to support progressive legislation.

• Erich Salomon (Germany) – Master of candid “available light” photography in political and diplomatic circles during the 1920s.

⸻

📷 Golden Age of Photojournalism (1920s–40s)

• Henri Cartier-Bresson (France) – Co-founder of Magnum Photos; refined the “decisive moment” approach, blending reportage and artistry.

• Robert Capa (Hungary) – Covered five wars, including the Spanish Civil War and D-Day; famous for frontline bravery.

• Margaret Bourke-White (USA) – LIFE magazine’s first female photographer; documented industry, the Great Depression, and WWII.

• Dorothea Lange (USA) – FSA photographer during the Great Depression; iconic Migrant Mother image.

• W. Eugene Smith (USA) – Known for deep, humanistic photo essays for LIFE, including coverage of Minamata disease in Japan.

⸻

🌍 Pioneering Agencies

• Magnum Photos (founded 1947 by Cartier-Bresson, Capa, George Rodger, David “Chim” Seymour) – Helped establish photojournalism as a collaborative, independent profession.

Here’s a timeline of photojournalism’s pioneers and milestones, showing how the craft evolved from the 1850s to the mid-20th century:

⸻

📍 1850s–1870s | Birth of War Photography & Documentary Work

• 1855 – Roger Fenton (UK) photographs the Crimean War — carefully posed to avoid disturbing the Victorian public.

• 1860s – Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner (USA) photograph the American Civil War, bringing stark images of battlefields to the public.

• 1860s–1870s – Felice Beato (Italian–British) photographs the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and conflicts in Asia — among the first to capture the aftermath of battle.

⸻

📍 1880s–1910s | Social Reform & Early Candid Work

• 1890 – Jacob Riis publishes How the Other Half Lives, using flash to reveal New York’s slum conditions.

• 1900s–1910s – Lewis Hine documents child labor and immigrant workers, influencing U.S. labor laws.

• 1910s – Early picture magazines like Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung begin pairing timely news with photographs.

⸻

📍 1920s–1930s | The Rise of the Illustrated Press

• Erich Salomon (Germany) perfects candid political photography using small cameras and available light.

• André Kertész (Hungary/France) experiments with personal reportage that blends art and journalism.

• LIFE Magazine (1936) launches in the U.S., making photo essays central to news storytelling.

⸻

📍 1930s–1940s | The Golden Age of Photojournalism

• Henri Cartier-Bresson develops the “decisive moment” approach; co-founds Magnum Photos (1947).

• Robert Capa covers the Spanish Civil War, WWII (including D-Day), and later conflicts.

• Margaret Bourke-White becomes LIFE’s first female staff photographer; documents industry, war, and the Partition of India.

• Dorothea Lange creates enduring Depression-era images for the FSA (Migrant Mother, 1936).

• W. Eugene Smith produces deeply humanistic photo essays for LIFE in the 1940s and beyond.

⸻

📍 1947 | Magnum Photos

• Founded by Cartier-Bresson, Capa, George Rodger, and David “Chim” Seymour — a turning point where photographers gained more control over their work and distribution.

⸻

If we move past the “Golden Age” of LIFE and Magnum, there’s a later wave of pioneers from the 1970s onward who reshaped photojournalism to fit new wars, new media, and new audiences.

Here’s a breakdown by era:

⸻

📍 1970s–1980s | From Vietnam to Global Human Rights

• Don McCullin (UK) – Iconic war photographer covering Vietnam, Biafra, Lebanon; known for unflinching depictions of suffering.

• James Nachtwey (USA) – Covered nearly every major conflict from the 1980s onward; deeply humanistic approach to war and famine.

• Susan Meiselas (USA) – Magnum member; documented the Nicaraguan revolution and human rights issues across Latin America.

• Philip Jones Griffiths (Wales) – His book Vietnam Inc. influenced U.S. public opinion on the war.

⸻

📍 1990s–2000s | Conflict, Crisis, and the Digital Transition

• Lynsey Addario (USA) – Reports on war, refugees, and women’s issues in Afghanistan, Iraq, Darfur.

• Tim Hetherington (UK) – Co-directed Restrepo; combined stills and film to capture soldiers’ lives in Afghanistan.

• Gary Knight (UK) – Co-founder of the VII Photo Agency, which gave photographers independence from big media outlets.

• Sebastião Salgado (Brazil) – Known for epic, long-term projects like Workers and Genesis, blending journalism with environmental and social themes.

⸻

📍 2010s–Present | New Voices & Multimedia Storytelling

• Damon Winter (USA) – NYT photographer known for intimate political and human stories; Pulitzer Prize for Afghanistan coverage.

• Carol Guzy (USA) – One of the few four-time Pulitzer winners; covers humanitarian crises worldwide.

• Marcus Bleasdale (UK) – Uses photojournalism to campaign against conflict minerals and human rights abuses in Africa.

• Moises Saman (Spain/USA) – Blends documentary and fine art to cover the Arab Spring and Middle East conflicts.

⸻

💡 What’s Changed

• Independence: Many recent pioneers formed their own agencies (e.g., VII, Noor, Panos) to control distribution and ethics.

• Multimedia: Short films, audio, and interactive pieces are now common tools.

• Long-form projects: Photographers often spend years on a single issue rather than chasing daily news.

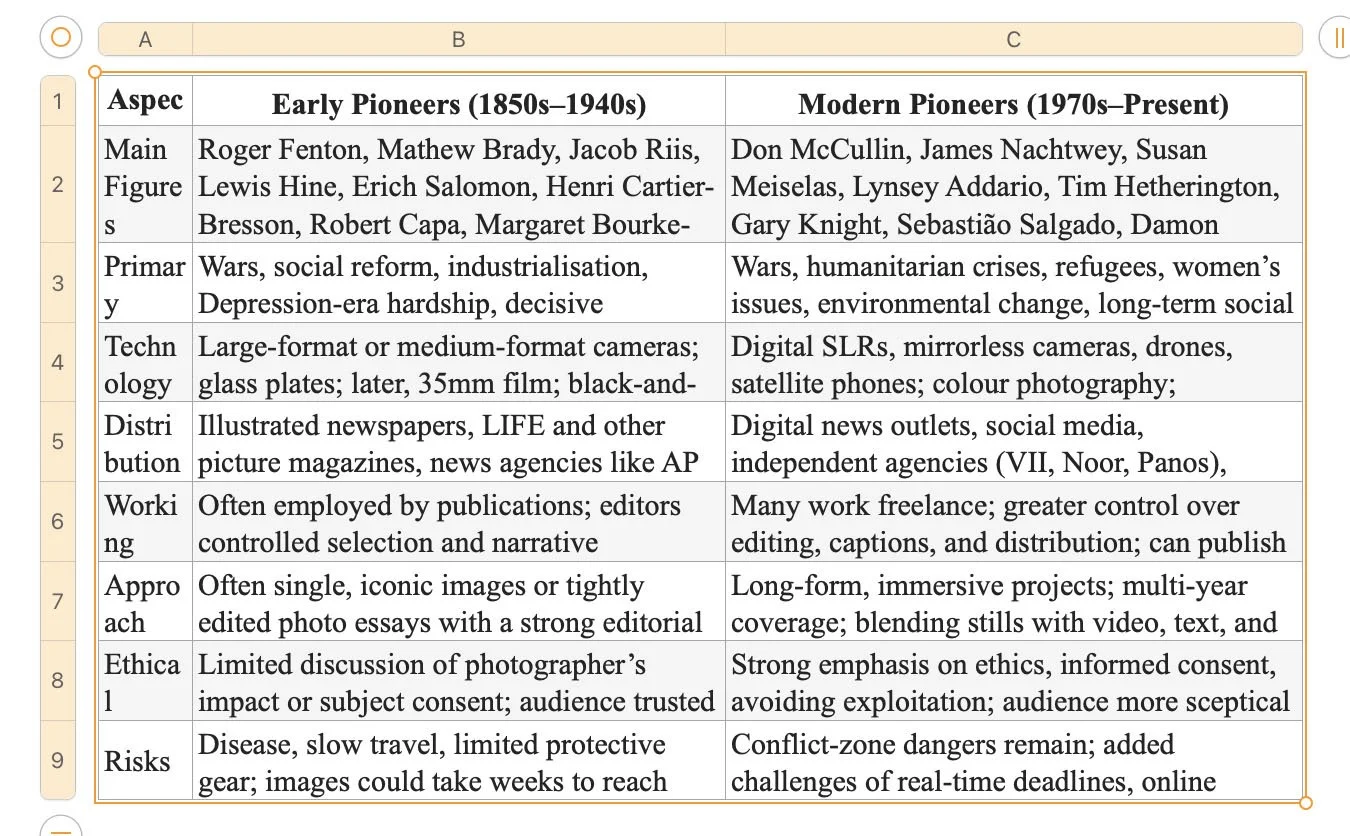

Here’s a side-by-side comparison of early pioneers vs. modern pioneers of photojournalism, showing how the craft, tools, and approaches evolved.

Documentary photography grew alongside — but distinct from — photojournalism.

While photojournalism focuses on timely news events, documentary photography often aims for in-depth, long-term storytelling about social conditions, culture, or change.

Here are the key pioneers, in roughly chronological order:

⸻

📍 19th Century Origins

• John Thomson (Scotland) – Street Life in London (1876–77) with journalist Adolphe Smith is an early example of combining images and text to document social life.

• Jacob Riis (Denmark/USA) – Used flash powder to photograph tenement conditions in How the Other Half Lives (1890).

• Peter Henry Emerson (UK) – Photographed rural life in East Anglia with a belief in “naturalistic” photography (1880s–1890s).

⸻

📍 Early 20th Century Social Reform Era

• Lewis Hine (USA) – Photographed immigrants, child labour, and industrial workers; his images were instrumental in passing U.S. labour laws.

• August Sander (Germany) – People of the 20th Century project, a systematic portrait of German society across classes and professions.

• Paul Strand (USA) – Brought modernist composition to socially aware projects like Time in New England.

⸻

📍 1930s–1940s | The FSA and Global Expansion

• Dorothea Lange (USA) – Iconic Depression-era portraits such as Migrant Mother (1936).

• Walker Evans (USA) – Captured architecture, interiors, and people of the Depression South with a stark, factual style.

• Gordon Parks (USA) – Documented African American life and racial segregation; later became a LIFE magazine photographer and filmmaker.

• Margaret Bourke-White (USA) – LIFE’s first female staff photographer, mixing documentary and photojournalism worldwide.

⸻

📍 Post-War Humanist Documentary

• Henri Cartier-Bresson (France) – Magnum co-founder; while also a street photographer, he produced long-term documentary essays across the globe.

• W. Eugene Smith (USA) – Known for immersive essays such as Country Doctor and Minamata.

• Robert Doisneau (France) – Chronicled postwar Parisian life with warmth and wit.

⸻

📍 Legacy and Influence

Many later photographers — Sebastião Salgado, Susan Meiselas, Mary Ellen Mark, and others — build directly on these foundations, combining the empathy of humanist photography with the rigour of documentary investigation.

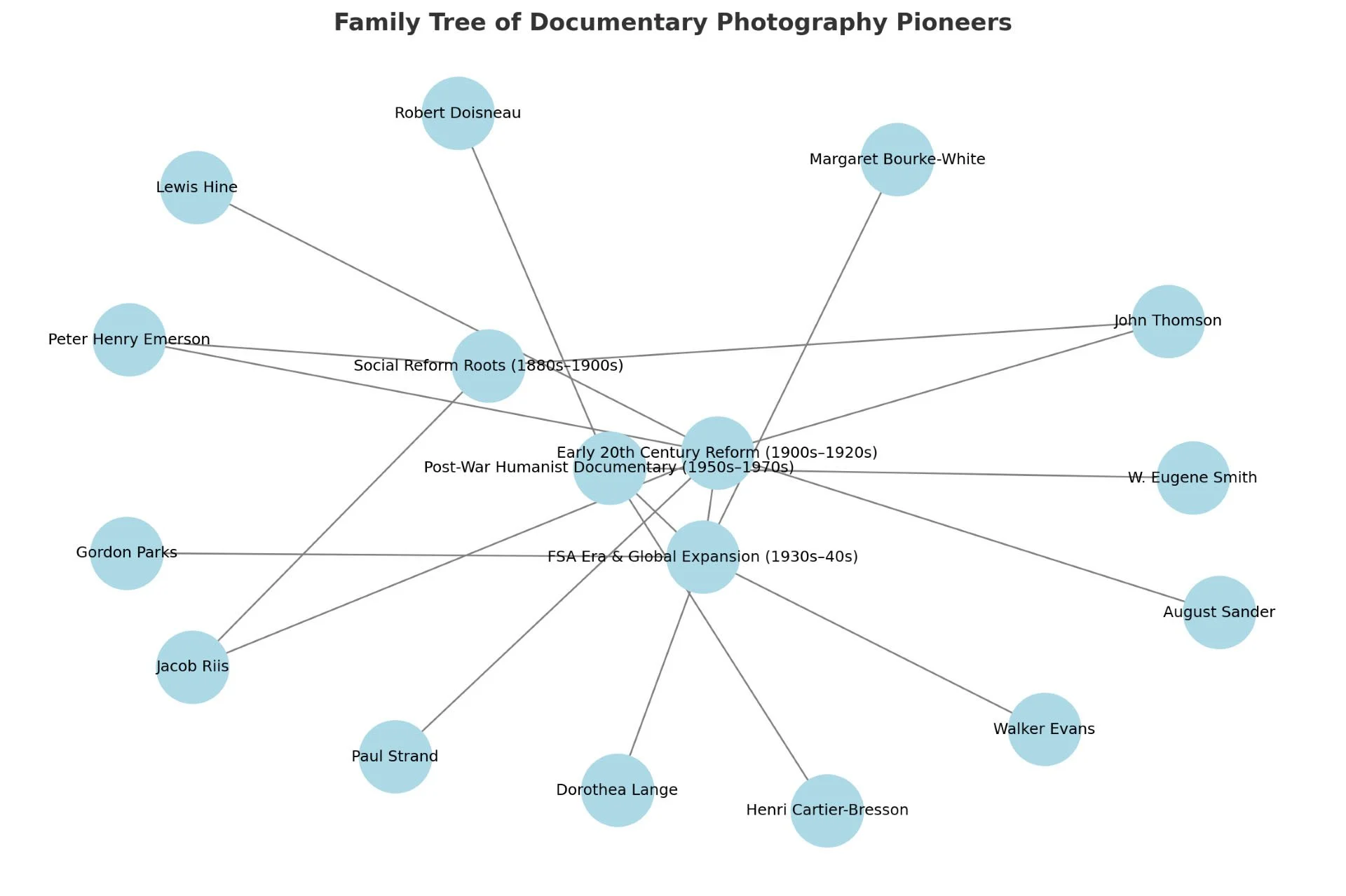

Here’s the family tree of documentary photography pioneers, showing how the tradition evolved from 19th-century social reform work to the post-war humanist era.

If we look at the recent pioneers — from roughly the 1980s onward — these are photographers who took the humanist, socially engaged tradition of documentary work and adapted it to new political realities, technologies, and audiences.

⸻

📍 1980s–1990s | Expanding the Humanist Tradition

• Mary Ellen Mark (USA) – Intimate, long-term projects on street children, mental health institutions, and marginalized communities.

• Sebastião Salgado (Brazil) – Large-scale, multi-year projects (Workers, Migrations, Genesis) blending beauty with social critique.

• James Nachtwey (USA) – Though often called a war photographer, his long-term documentation of poverty, famine, and disease fits squarely in documentary tradition.

• Susan Meiselas (USA) – Known for Carnival Strippers and later documenting revolutions and post-conflict societies in Latin America and Kurdistan.

⸻

📍 2000s | New Media & Global Scope

• Lynsey Addario (USA) – Works on women’s lives in war zones and humanitarian crises.

• Ami Vitale (USA) – From conflict zones to wildlife conservation; focuses on interconnectedness of people and environment.

• Marcus Bleasdale (UK) – Long-term work on conflict minerals and human rights abuses in Central Africa.

• Ed Kashi (USA) – Combines still photography, video, and multimedia to tell stories about health, ageing, and oil exploitation.

⸻

📍 2010s–Present | Multimedia & Participatory Storytelling

• LaToya Ruby Frazier (USA) – Uses personal narrative and community collaboration to document deindustrialization, environmental injustice, and family history.

• Zanele Muholi (South Africa) – Visual activist documenting LGBTQIA+ communities in South Africa with a participatory approach.

• Heba Khamis (Egypt) – Focuses on social taboos and underreported issues, such as breast ironing in Cameroon.

• Kiana Hayeri (Iran/Canada) – Long-term work in Afghanistan on youth, gender, and societal change.

⸻

💡 What’s New Compared to Earlier Generations

• Longer commitments: Many spend years embedded in a single community or topic.

• Multimedia storytelling: Film, audio, VR, and interactive web features expand the form beyond still images.

• Collaboration: Subjects often contribute to shaping the narrative.

• Global reach: Distribution through social media, independent platforms, and direct audience engagement.